The Pile of Debris before Him Grows Skyward: Chen Ching-Yuan

Image Courtesy: Chen Ching-Yuan

There is now a global current of young artists deploying the codes of history painting, drawn to the unpredictability of premodern affect as well as to the political potential of stepping outside of a contemporary framework. Chen Ching-Yuan first turned to this classical genre as a black hole of meaning, as a way of thinking through the complex turns of colonialism, postcolonialism, and neocolonialism. The symbolically loaded tableaux he found appeared ripe for rearranging, or for getting lost inside. The resulting casual absurdity of Chen’s work is destabilizing; it quotes individual compositions and moments from history just slyly enough that the viewer can never quite put a finger on a specific reference. In inserting his paintings into the discourse of art, he refers to a synthetic history and reclaims the plasticity of the past we all think we know. As a result, painting becomes an ahistorical artifact, simultaneously belonging to the now and to any number of past moments.

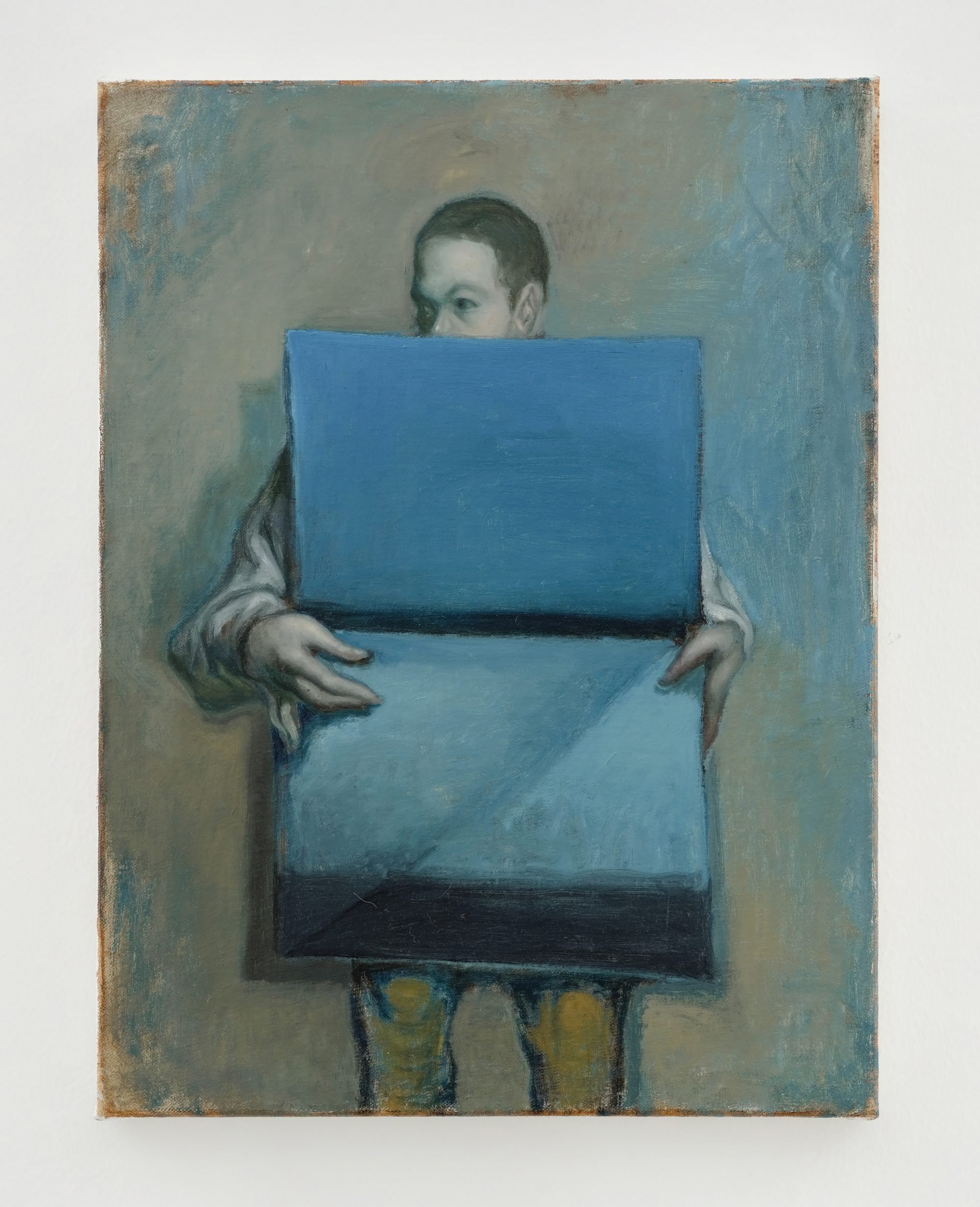

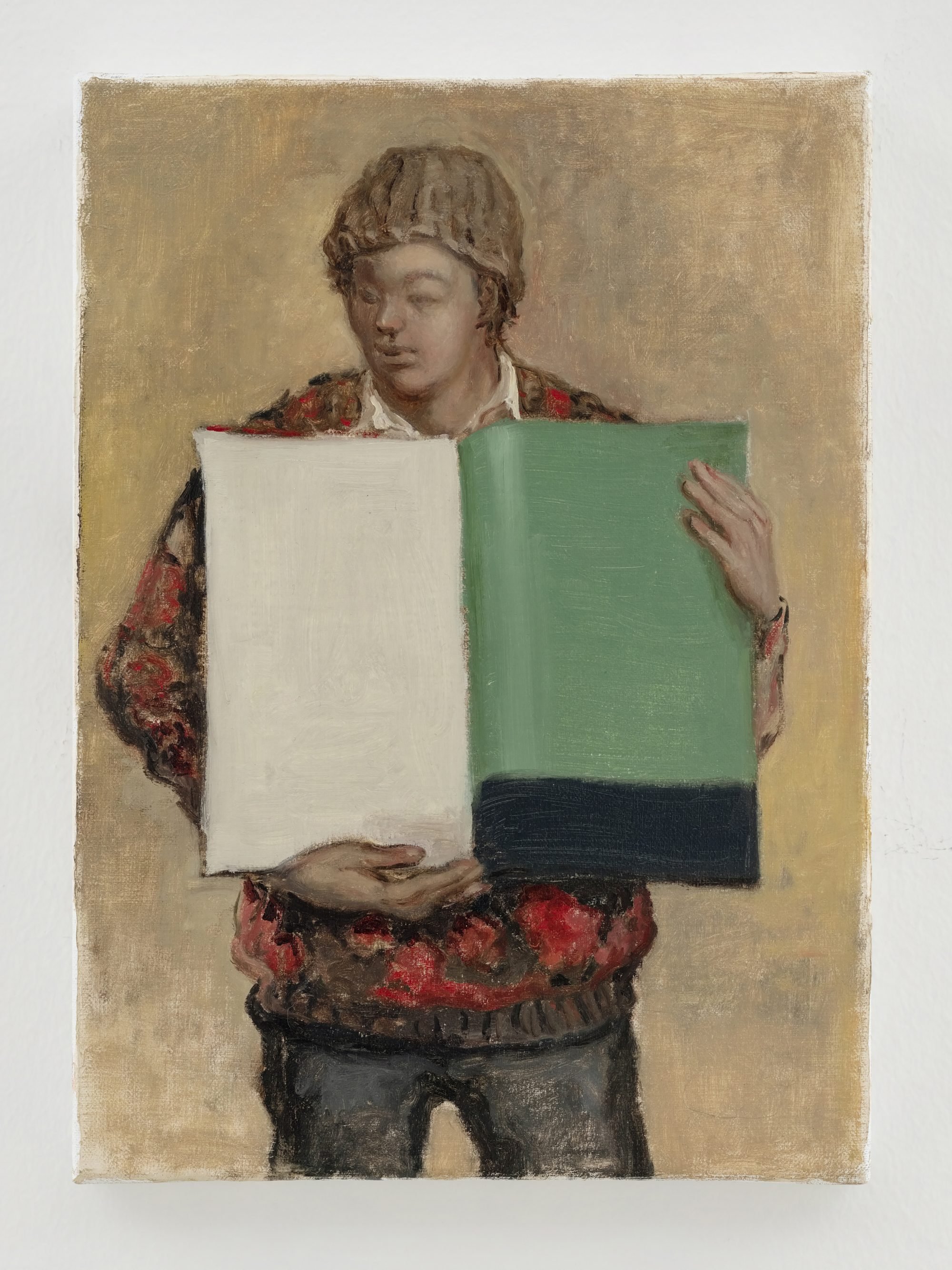

Chen Ching-Yuan began to strip away the layers of mythology that had accumulated over his quasi-historical compositions with the series Card Stunt, which dominated his production from 2018 to 2020 and peaked in an exhibition of the same title at mor charpentier, Paris (2019). Inspired by the mobilization of bodies as display technologies in art forms like North Korea’s Mass Games or China’s Beijing Olympics opening ceremony, these paintings depict people holding monochromatic cards. Chen chooses a middle distance, framing one or several individuals but never enough to reveal the pattern or image that would be shown on a critical mass of cards seen in totality, and never so close as to become a portrait. These figures are typically indistinct. As with the facial features and costuming in the bulk of his paintings, they come from an unclear time and place, not obviously bound to a certain group or culture. The artist is clear that it takes a certain kind of social structure to treat a person as a pixel, and that the transformation of spectatorship into a form of labor says something about the nature of art.

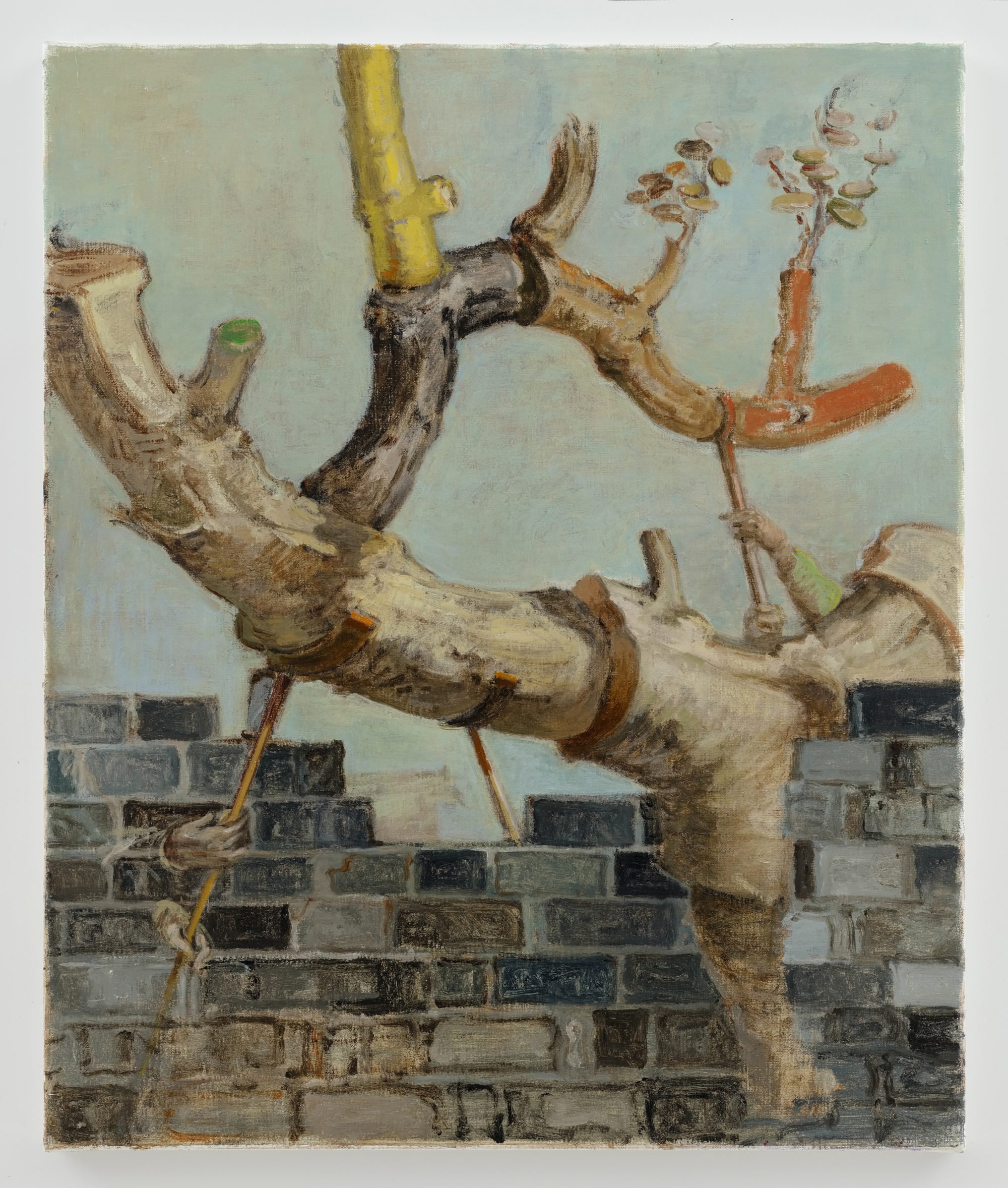

Throughout 2020 and 2021, Chen has been focused on Timber and Brick, two intertwined series that were first shown in an online exhibition at White Cube (2021). In Timber, small groups of men employ harnesses, slings, and their own gloved hands to put together or take apart the trunks and limbs of trees. Most of these parts are cut into thick sections, and most of the sections are painted in unnatural primary colors. It appears to be a crude form of surgery, whose goals—if this labor has a point at all—are unclear. Branches read like bones or human limbs, cut apart only to be sutured back together. Some of them grow through gaps left in brick walls, while others grow over the tops of irregular walls, supported by structures placed for this purpose.

In Brick, the bricks that constitute these walls take center stage. On small canvases measuring twenty or thirty centimeters to a side, Chen depicts configurations of blocks almost at life size in a bleak palette that recalls nothing so much as the still lifes of Giorgio Morandi, a semiotics of everyday texture that only demurs the longer it is analyzed, gently insisting on its vacuity. The particular constellations seen here, however, might be familiar: standing in arches or low towers, these are the technologies of resistance deployed during Hong Kong’s long 2019 and 2020, left behind in the streets as protestors retreated in order to delay pursuing police vehicles. Working at this size, the viewer’s sense of scale is lost; the bricks look at times monumental and at times diminutive. They are both fragile and lasting, art objects found in the wild and preserved within these pictures.

A handful of more recent paintings begin to focus on the labor of the everyday—domestic tasks like cleaning and organizing—indicating a new direction for Chen. The Gloves (2021) carries on the elbow-length thick rubber gloves of the Timber series, depicting gloved hands scrubbing floors or performing PCR tests through a divider. In the triptych Study of Flattening(2021), a figure glimpsed partially through aluminum blinds is depicted three times, on each occasion wearing a different-colored shirt and working on a different-colored ironing board. The images are otherwise nearly identical: an exercise in drapery and shadow. Chen is interested in color as a store of political meaning, in the sense that certain shades are associated with particular political parties, or certain dyes were once restricted to the upper classes. What now remains is this matrix of references without any real-world referent.

Cards, tree limbs, bricks, gloves, and now ironing boards: in their repetition and palette these planes and volumes take on painterly meaning; indeed, they are more moments of painterliness than objects depicting narratives via compositions. Taken collectively, they distill something essential about the nature of painting. Over the past five years Chen has metabolized the knotty mythologies of the history genre into anecdotes alienated and displaced from all that, slowly turning toward these singular units that can be swapped out, borrowed, reconfigured, and put into dialogue. If this monadic order emerges from the atemporal stuff of the past, it borrows its cold sense of humor from Chen’s own formative experiments with animation. There is a kind of code here, its terms absurd and divorced from definition. It’s a dry sort of comedy in which the setup and the punch line are interchangeable, but it seems that’s exactly what the angel of history has turned out to be.